National bestiary

27 June 2020

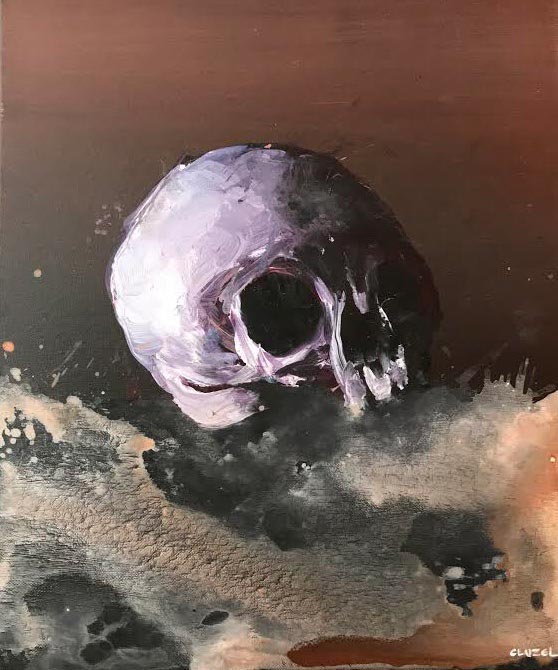

Mechanisms of Defense

29 June 2020Nicolas Cluzel

STATE OF EMERGENCY

SEPTEMBER 13th – NOVEMBER 17th 2018

PRESS RELEASE

STATE OF EMERGENCY

The present show consecrated to Nicolas Cluzel tells us about the general state of emergency in which our so call western societies currently are. The french term “État d’urgence” (State of Emergency) refers to the measures that had to be taken in 2015 by the French government of François Hollande after a serie of terrorists attacks that allowed authorities to restrict civil rights such as trespassing for a home search without a warrant or banning street demonstrations.

That very term, evoke the increasing tension raised by the different crisis that western countries are facing nowadays, along with the general concern about what it feels like a derailing civilization: migration wise, economy wise or cultural identity wise. Cluzel embodies all of them perfectly on canvas. Yes indeed, Nicolas Cluzel paint storms, disasters, hordes, clashes and fights unraveling for us the state of emergency of humanity.

Yet sailing in the open sea or close to the shore, we recognize today’s immigrants thriving for a better life; behind its iPhone taking a selfie we identify the new generation of slaves of consumption; streapteasing before a famous masterpiece we think about Femen actions. Everything there is topicality and push us to meditation. Nonetheless, the artist doesn’t want to take openly part in a politic way but just to observe facts and translate them into pigments and canvas for us.

That’s why he uses a fresh quick expressionist style. Avoiding correction, he needs to expand himself applying the acrylics and waving his brushes with intensity so his voice can be heard. The emergency couldn’t be better expressed so, making us face how sudden are the dangers we are exposed to as citizens of the world, this world, yes, because is the artist who put them on that scale. Beyond the inherent monstrous side, his characters are whimsical, flighty, beyond all bearing, like if they were always trying to get away with it, so to speak. Thus, they invade canvas becoming the core of the topic, along with the texture, like if just the urge of existing were what worries them.

Nicolas Cluzel amuse himself reinterpreting masterpieces, making pastiches of Goya, Caravaggio or Delacroix, being this dialog between Masters what allows him to focus the present confronting different points of view. Once revisited, these very well known masterpieces, become something else. Some of us will see a mere critic to our time on them and some, just an stylistic reinterpretation but the truth is that, being inspired by his predecessors, the artist frames the relevance of the painting related to social context. As gallerist and defenders of freedom of expression, we want to nurture a realm where opinionated artist as Nicolas Cluzel can freely express themselves.

BIOGRAPHY

NICOLAS CLUZEI

Nicolas Cluzel was born in 1987 in Angers. He currently lives and works in Lyon. He practiced drawing and comics for years before dedicating himself to painting. After a Masters in Applied Arts at the University of Provence (Aix-en-Provence), Nicolas began to exhibit in various artists’ fairs and group exhibitions across France. Since then, several galleries have represented him in Bordeaux, Marseille, Aix-en-Provence and Lyon. Tournemire Gallery devoted his first exhibition to him abroad (Madrid, Spain).

Individual exhibitions

2018 Galerie Tournemire (Madrid, Espagne)

2018 Galerie Jérôme B (Bordeaux)

2017 Galerie L’Âne bleu (Marciac)

2016 Galerie Le cœur au ventre (Lyon)

2015 Galerie Fert (Yvoire)

2013 Galerie Anna-Tschopp (Marseille) 2

2011 Galerie Vincent Bercker (Aix-en-Provence)

2010 Galerie La Tourette (Tournon sur rhône)

Group exhibitions and fairs

2018 Passage à l’art (Cherbourg), Centre d’art Chaillioux (Fresnes)

2017 Galerie Jérôme B. (Bordeaux), Galerie Anna-Tschopp (Marseille)

2016 Galerie Brulée (Strasbourg), Galerie Le coeur au ventre (Lyon)

2017-2015-2014 MAC PARIS (Paris)

2016 Figuration critique (Paris)

2015-2013 Puls’art (Le Mans)

2014 ArtCité (Fontenay-sous-bois)

2012 L’Arrivage (Troyes)2012 “L’Humanité” (Beaulieu – Lausanne – Suisse)

Interview to Nicolas Cluzel,

Madrid 10/27/18

« I like the idea of Tragicomic »

Tournemire Gallery – The first remark that someone makes when contemplating your work is necessarily based on the numerous references from which your inspiration is nourished. Why are you so interested in classical painters?

Nicolas Cluzel – There are different reasons to inspire, quote and honor artists from the past. One of the main ones is, allegedly, sentimental based because I like the works of those painters. Then there is a purely plastic and aesthetic dimension; I can be inspired by a painting only because I am interested in its composition or its light. Another focus of interest comes from the initial subject in the painting. It is not by chance that Caravaggio painted beheadings, that Goya taught the absurdities of his time, or that Rubens performed a “massacre of the innocent” with so much movement and violence. For me, the initial subject intervenes as a triggering element in my own practice to show what I feel talking about at this precise moment. Another aspect, finally, comes from a type of resistance where we young painters do not forget where we come from. Referring to classical painting is a form of aesthetic resistance in an age of image abuse, and media. Regarding that, I am all for the making of sensitivity, subjectivity and singularity.

T.G. – Talking about the current exhibition, you make use of great masterpieces to give us your own vision of the current world. In that sense, do you seek to deliver a clear and unequivocal message, or do you leave the viewer free to reach their own interpretative conclusions?

N.C. – A bit of both. This is just what my work is all about. Depending on the context of making, an image can have different meanings. For me, painting cannot be limited to being narrative but must represent its time. This is where my doubt comes from … How can you talk about your time without being compromised and, consequently, send a clear message? Matisse said that painting had to be used for something other than painting. It is true, the pure pictorial does not interest me. Painting has to embody something, a form of external reality. If this reality has a powerful background and content that refers to our time and its problems, for example, the it is relevant to me. We speak here of an expressive, living painting, with an existential or political content, although I always feel divided between form and background, between the pigment and the subject (…).

T.G. – The references to the great painters are undeniable, but your style remains, even a cursory glance instantly recognizes your hand. Do you appreciate the term Expressionism as a qualifier of your work, and, in that case, why do you consider yourself more drawn to that style than to another?

N.C. – If we understand expressionism as the pictorial expression of a suffering inner self, then this term does not interest me. I do not feel affiliated to a practice that would reduce painting exclusively to the expression of interior existential anxieties. When I started painting, I was more leaned to that but nowadays I think I have understood, step by step, that you don’t have to be pathetic to be subjective. Painting is the expression of an artist, it is evident, but I don’t think we can keep ourselves on that. In spite of everything, I like the expressionism of Goya’s last stage and of the expressionist movements of the beginning of the 20th century.

T.G. – Apart from the references and the personal invoice, your characters also stand out for their particular appearance. Are you influenced by your training as a comic artist when conceiving your characters?

N.C. – The comic has influenced me before, yes, although much less now. What interests me about caricature is, above all, the idea of exaggeration, the facility of the medium to harden and distort the features. This does not mean that I question the idea of harmony or the balance of Beauty, it is just that I consider that the time in which we live, Beauty is conspicuous by absence. If the bodies are deformed or mistreated, it is largely because I like to paint flesh. In David Cronenberg’s work, for example, the flesh is the demonstration of our existence, dirt for dirt has no interest, there is a philosophical dimension behind all this. We are animal meat, that’s what it says.

T.G. – One canvas stands out from the others, the work “Tempête”, in which you abandon your characters in a stormy storm landscape, close to abstraction. Is it a pictorial investigation indicative of a direction in which you plan to orient yourself?

N.C. – “Tempête” is a particular painting, it is true, because it no longer represents Man but rather teaches the chaos in Nature. Be careful, it is not an abstract painting! To abstract means to extract the substance, the pictorial for the pictorial and that does not interest me. It is, however, the theme of the storm and circumstantialy the landscape, which touches me along with the Still Life. It is another way of talking about Man and the times we live in.

T.G. – Goya is one of your main inspirations, an artist who was always highly critical with his time and who denounced the excesses of society. Do you also see yourself as what we could call a protest artist?

N.C. – This question is difficult and takes us to square one. I speak of contemporary events, yes, such as the notion of power, the migratory flow, religious and political extremism, etc. but I don’t feel like a protester! Answering is when you go against something. My idea here is to disturb and not to constrain myself to a bounded line. It is above all about painting, I am not in militantism. I feel more critical than protester, I use irony to mislead while putting my finger on the sore spot.

T.G. – There isin your work a scent of violence; a violence that, on the other hand, partly defines our current world. Would you say that as a painter you are obliged to represent that violence, is it a duty for you?

N.C. – I think that the artists are here to question. They commit to their subjectivity and share it with the public. His subjectivity resonates with the world. This world may adopt external signs of violence, as in my case, but it is a ridiculied violence. I like the idea of the tragicomic because, in the end, we only have the laughter left. As the philosopher Clément Rosset said “there is a lot of seriousness in our parties”. Laughter helps put distance while keeping the burden of truth, it is also liberating and allows to relieve while talking about very serious things. The titles in my paintings summarize it well. In the end, violence is less present in my paintings than in reality (…).